Your style is where you fell short but kept going anyway.

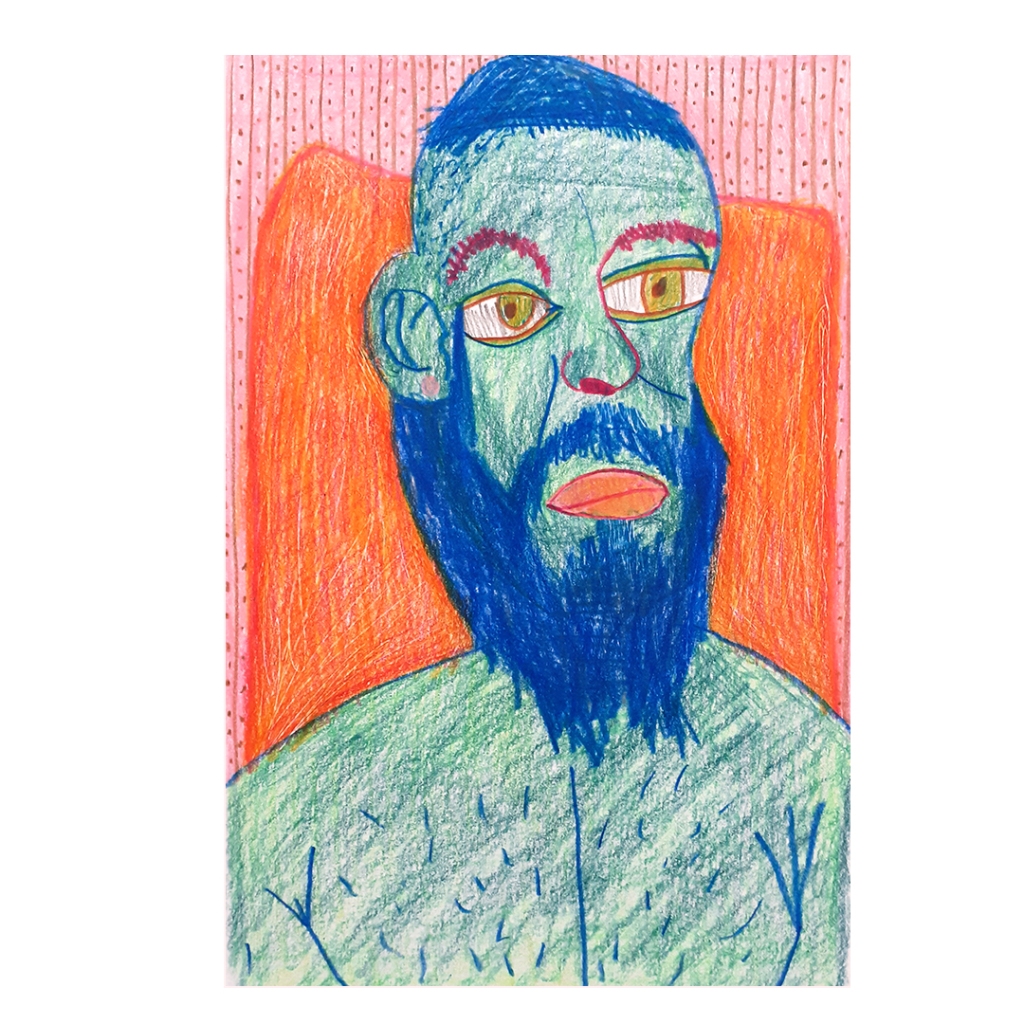

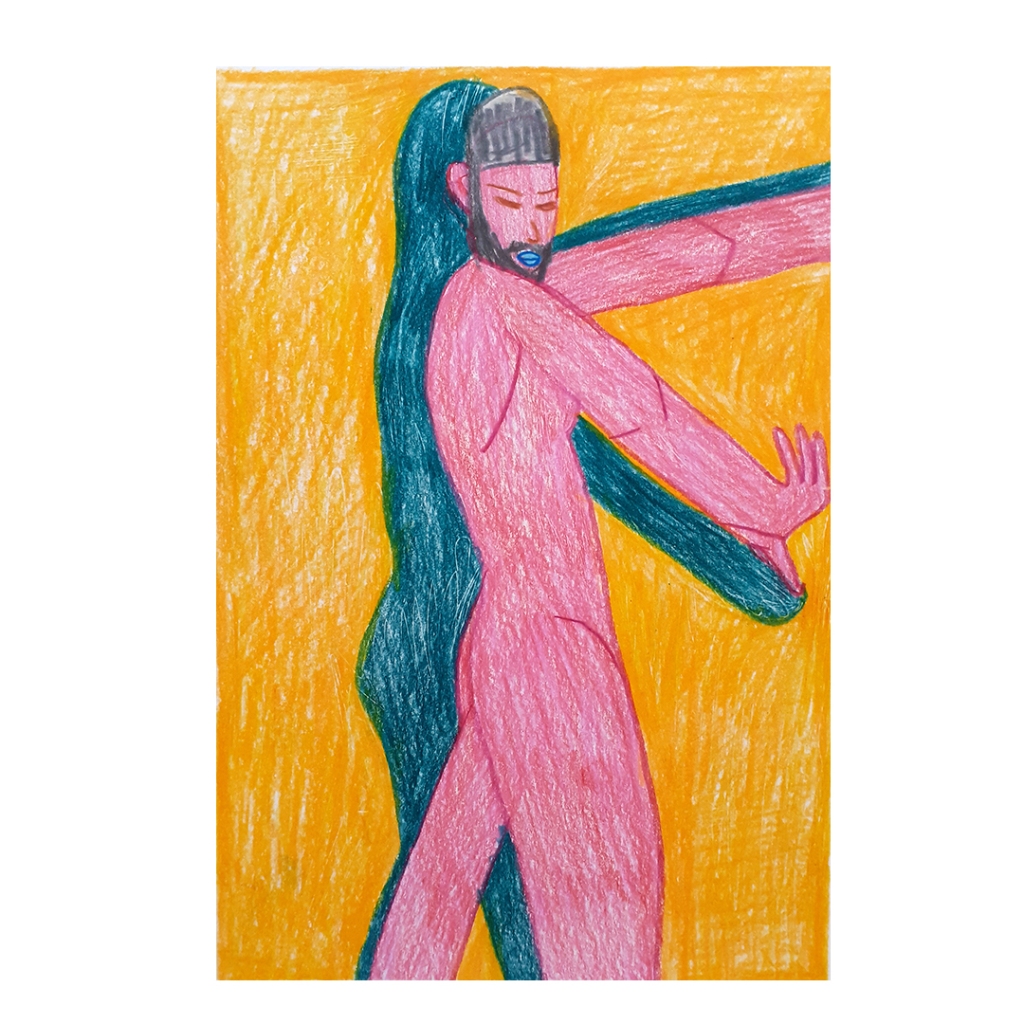

I’m not sure that’s true but at the moment it feels like it might be. You aimed for something and you couldn’t do it but what remains is the thing they call style. I say this because someone said “I like your style” and I thought: Style? I can’t even draw! I’ve been learning to draw. At the moment it’s life drawing. I attend regular life drawing classes online and I fall short.

I want to draw the human figure the way the human figure should be drawn, the way it’s drawn in what I guess you’d call traditional ways. Of course, there are also moments when I think, no, that’s not what I want. I just want to have fun and play. I want to see what I can do with what I have, with what comes naturally (if there is such a thing). Maybe that’s what style is. If you’re having fun, that’s probably a sign you’re writing or drawing or painting in a way you feel at home in. Despite and maybe because of that nudging nagging feeling that I should be doing it properly. I should be writing great family sagas, historical dramas, doing what Jane Austen did, what Dostoevsky did, what VS Naipaul did, what all those robust writers did. Big grand novels. What Caravaggio did, Virginia Woolf, even, Picasso, even, if you look at his earlier work, at Hilma af Klint’s earlier work. But you look at their earlier work, even the work of Kandinsky, for example, and you realise that what they were doing at the beginning was not their style, or at least the style they are known for.

Style is the opposite of tradition. Or a conversation with tradition. Or a refuting of tradition, a skill for those who once did it the traditional way. At some point we thought that’s what writing should be. Traditional. Tradition was all we had to refer to, at least most of the time. It’s what everyone was doing so should we be doing it too, writing like that, drawing like that, painting like that. As I gradually immerse myself in the world of drawing and illustration (not yet painting, still not) I feel how there is much more room for the non-traditional, in a way that I’m not sure writing or literature has many examples of. Maybe it’s to do with how we think of language, what we expect when we open a book, what you can actually do in a book made up of only words.

Sometimes I feel like that I can’t draw, not in the traditional way, not with much skill. When it comes to writing it’s a bit more complex. I studied literature. I read a lot, more in teh past than now, but still. Question: Is the link between looking at paintings and painting per se (I love that expression: per se! So archaic, such chubby cheeks to pinch) the same as reading is to writing? Maybe looking closely at paintings for the past many years has been some kind of groundwork, some kind of permission to play and to tell myself that this might be my style, and then to keep doing it, and by doing it become better at it.